(Rivista

Internazionale - December 1999: Celebrations

for the Orderís Ninth Centenary

- 1/3)

Celebrations for the Orderís Ninth Centenary

WORLD GATHERING IN MALTA

This historic event was solemnly celebrated on every continent by all the Orderís national and international bodies with commemorative ceremonies of a religious nature and international meetings. State and official visits were also made and received by H.M.E.H. the Prince and Grand Master, with the other High Offices of the Order. There were working meetings of the Orderís various bodies, of both a spiritual and operational nature, with the inauguration of hospitaller and first-aid structures, historical museums and study conferences as well as the establishment of cultural centres.

|

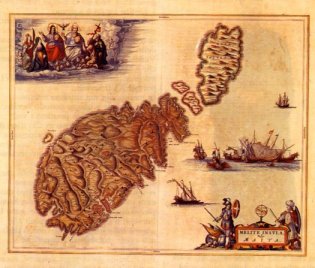

| Water-colour Map of the Island of Malta (1662). |

The Orderís Jubilee Year was opened in Malta on 4 December 1998 with a World Gathering in which around 1000 Knights and Dames from all over the world participated.

The salient events of this meeting, which was given ample space in the previous edition of this Rivista and in the media, were:

- The Pontifical Mass celebrated by the Cardinalis Patronus, His Eminence Pio Laghi, in the co-Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Valletta attended by H.M.E.H. the Prince and Grand Master, the President of the Republic of Malta and members of the Diplomatic Corps.

- The Plenary Assembly presided over by H.E. the Grand Chancellor, Amb. Conte Don Carlo Marullo di Condojanni, at the Mediterranean Conference Centre.

- The signature of the Fort SantíAngelo agreement at the Presidentís Palace by the Grand Chancellor and the Prime Minister of the Maltese Government.

Three separate sessions were held in the World Gathering: the Grand Priors and representatives of the Members in Obedience co-ordinated by H.E. the Grand Commander, Ven. Bailiff Fraí Ludwig Hoffmann von Rumerstein; the Presidents co-ordinated by the Grand Hospitaller, Baron Albrecht von Boeselager; and the Ambassadors co-ordinated by H.E. the Grand Chancellor. The conclusions were presented to the Ordinary Chapter General this June.

A high point was the historical lecture given by Prof. Giovanni Morello in the Mediterranean Conference Centre in the presence of H.M.E.H. the Prince and Grand Master and all participants in the Gathering:

Most Eminent Highness, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Confreres,

It is a great honour, but also a difficult task for me to address this expert and important assembly, met to celebrate the ninth centenary of the Orderís foundation.

I have been asked to retrace the steps that led to the birth of the Sovereign Military Order of St. John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, rereading the chronicles and documents of the Hierosolymitan institution from its foundation to these last years of the 21st century. I will do so by analysing the studies on this demanding subject, certain of your generous attention and benevolence in forgiving any involuntary lacks and oversights.

Studies - not always recent, apart from some excellent summaries of the Orderís history which appeared relatively recently and which are worth examining - provide information and useful indications for establishing the origin of the Hierosolymitan Order and the date of its birth, although no indisputable documentary evidence exists. However, certain clues and an unbroken tradition point to its foundation at the time of the conquest of Jerusalem by the Crusaders.

It has been rightly observed that the origins of millenary institutions are often obscured by the mists of time and left like this as power and wealth were gradually acquired, in case the simplicity or humbleness of origin could in some way diminish the splendour and grandeur achieved. This also applies to the Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, whose origins are interwoven with the complex development of relations and clashes between Christians and Muslims in the land in which Our Lord Jesus Christ spent his earthly life.

The ancient chronicles and modern historians seem, however, to agree on the essential events of the birth of the Order of the Knights of the Hospital in Jerusalem. Both the most accredited researchers into the Orderís history and the modern historians of the Crusades, like Franco Cardini, François Chalandon, Steve Runcimen and Kenneth M. Setton, are all agreed that the Order first began in Jerusalem as a charitable foundation assisting the pilgrims who came to pray in the Holy Land and to visit the places where the most significant events of Our Saviourís life and passion took place.

According to ancient testimonies, it was all started by a group of merchants from Amalfi, one of the main centres of commerce with the East, which monopolised dealings with Egypt and Syria. About the middle of the year one thousand, these merchants had obtained from the Caliph of Egypt, under whose authority Palestine was then placed, a concession for building a church and a hospice, or hospital, to receive the sailors and merchants of Amalfi who periodically came to the holy city on business. This date is considered very probable because in the same year 1050 the Doge Mauro of Amalfi had established a documented, similar foundation in Antioch of Syria.

The foundation was established in the Christian quarter, delimited by walls (completed in 1063), which was the only part where the Christians could stay in Jerusalem. It occupied about a fourth of the area of the entire city, and the Amalfi merchants built the church of Santa Maria Latina there with connected hospital.

Without going into archaeological dissertations, it is known that these buildings were situated in front of the church of the Holy Sepulchre, and it is from these that the future hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem made their first moves. Very soon the merchants of Amalfi were joined, as guests, by the pilgrims of the Holy Sepulchre who had never stopped going to pray on their Saviourís tomb, even in the difficult times of the Muslim occupation of the city. They were housed in the hospice, or hospital, of the Amalfi foundation, dedicated according to some to St. John the Almsgiver, patriarch of Antioch in the 6th century - albeit there is no certain basis for this - continuing a much older tradition.

The presence of hospitals, or xenodochium in the old meaning of the word, as a place of hospitality for pilgrims who needed rest and care after the difficulties and length of the journey, is documented in Jerusalem from very ancient times. In the 6th century, St. Gregory the Great had invited a religious called Probo to the city to build a hospice there, not only for pilgrims but for all the poor; a second hospice was established on Mount Sinai.

The conquest and re-conquest, with their wake of violence and persecution, of the Holy Places between the 7th and 8th centuries certainly made it a dangerous area for Christians and pilgrims. In 614 the Persians of Cosroe took possession of Jerusalem, ten years later the Emperor of the Orient Heraclius won it back again for the Christians. But in 636 Jerusalem fell under Muslim domination and the Christians were once again threatened.

It was only during the enlightened reign of the Caliph Harun-el-Rascid that the persecutions against the Christians slackened off, so much so that diplomatic relations with the Muslims could start to recover. This began with Pippin the Short, who sent an embassy to the Saracens. Even more active was his son, Charlemagne, who at the end of the 8th century obtained a kind of protectorate over the Holy Places from the caliph and permission to build new churches and establishments in Jerusalem. Among these there was a hospice, or hospital, the continuation of Gregory the Greatís foundation, new or rebuilt, alongside which was also erected a church dedicated to Santa Maria and officiated by Latin monks, or Benedictines.

"From Emmaus we went to the holy city of Jerusalem, and we were received in the hospital of the most glorious emperor CharlesÖ" the monk Bernard, pilgrim to the Holy Land, narrated in Latin around 870, noting that: "beside it is the church of Santa Maria, which has a very rich libraryÖ"

After the destruction of the Holy Sepulchre and many other Christian buildings in Jerusalem, by order of Caliph Hakem Biamrillah in 1010, the church of Santa Maria Latina was also rebuilt and the hospital started to function again. Considering the short time elapsing between the destruction of the Christian buildings and the reconstruction of the Holy Sepulchre, undertaken by the Emperor of the Orient, Constantine IX, in 1048, the affirmation of the chronicler, Eccard, that in 1101 the hospital had never ceased to function in Jerusalem can be taken as true.

It was after the death of Hakkam, and the change in the attitude of the Fatimid Caliphs of Egypt towards the Christians, that the Amalfi merchants obtained authorisation to found the new institution; or rather to restore the existing one founded by Gregory the Great and reconstructed on the orders of Charlemagne. What is certain is that the two institutions were both situated near the Holy Sepulchre, beside the church of S. Maria Latina. As I said before, the ancient sources are in agreement on the fact that the hospice was founded by Amalfi merchants.

Amato of Monte Cassino, in his Líystorie de li Normant, written between 1078 and 1080, talks of Mauro "un noble home de Malfe (Amalfi)" who "avoit fait cert hospital en Antioce et en Jérusalem". Since the oldest test of his chronicle has come down to us not in Latin, but in a very bad French translation, preserved in a late manuscript dated between the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th centuries, some historians have insinuated that the relative passage on the foundation of the Amalfi merchants in Jerusalem could have been inserted later, perhaps by the translator. But there is no proof of this, and in any event there are other testimonies agreeing with it.

Sicardo, bishop of Cremona, who at the beginning the 2nd century accompanied the Pontifical Legato in Armenia and visited the Holy Land, recorded the foundation of the hospital of the Amalfi merchants, but dates it later around 1086. This is the date that some modern historians indicate as the foundation of the Hierosolymitan institution, but no document can confirm that the Amalfi foundation is actually the Hierosolymitan one, nor in Sicardís text is there any reference to the presence of Blessed Gerard.

The Amalfi foundation mentioned in the Chronicon Sicardi Cremonensis, published by Muratori in the corpus of the Rerum Italicarum scriptores, is corroborated by an anonymous fragment of a chronicle probably written precisely in Amalfi, according to Ughelli, who published it in his voluminous work entitled Italia Sacra.

It was, however, William of Tyre who provided the most interesting information on the birth of the foundation of the Amalfi merchants and their hospital, from which he made the Order of St. John of Jerusalem directly derive. William, first archdeacon (1167) and then archbishop (1174) of the city of Tyre, was born in an unknown place in Syria and his life was directly involved in the events of the Holy Land halfway through the 12th century. Because of the important role he occupied in the Catholic hierarchy, William could be considered one of the most privileged observers of the political and military affairs of the Latin Kingdom in the Holy Land.

Albeit William of Tyre was not particularly in favour of the Order of Hospitallers, and thus not considered very objective by the historians within the same Order, he did link the birth of the Order to the Amalfi foundation. Moreover, he was the first writer explicitly to indicate Blessed Gerard as the founder of the Order. William of Tyreís History was not only reworked and translated but was also the source of many other mediaeval chronicles on the history of the Holy Land, such as those of Jacques de Vitry or Marino Sanudo, which did not however add anything new to the affairs we are interested in.

In addition to these so-called external sources there were the internal ones, and especially two of them, the Exordium Hospitalis and the Miracula. The Miracula is a collection of legendary stories about the birth of the Order, often found inserted in its Statutes, but which also contains historical facts, such as the siege of Jerusalem by the Crusaders (1099), the mention of the two first Grand Masters, Gerard and Raimondo de Puy, and the confirmation of the statutes by Pope Innocent II (1130-1143). The text of Miracula, which was written around 1140-1150, refers to imaginary episodes and events linked to three epochs of the Old Testament, the New Testament and the First Crusade, which more directly touches the birth of the Order.

Although the first and second group of events immediately revealed their fanciful and miraculous nature, not without that taste for the marvellous that is found in many medieval legends, the third group has a more precise historical connotation. It was perhaps this which gave the Miracula an official investiture as a text approved with a bull of Celestine III of 16 July 1191, later renewed by many of his successors, and finally inserted in the collection of Statutes. Innocent IV, with a bull of 9 April 1254, had even legitimised part of these legendary tales, asserting that the building where the hospital had been established in Jerusalem was the same which had been glorified by the presence of Our Lord and his Mother after the Ascension.

A deliberation of the Chapter General held in Rome in 1445 at the time of Pope Eugene IV, albeit acknowledging as "foolish fables" many of the legends on the Orderís origins (dated back even to the time of Judas Maccabeus), confirmed the salient points of the life of Jesus narrated in the Miracula and proposed the hospital building as the place where the last supper had been held.

|

|

Malta. Valletta. H.M.E.H. the Prince and Grand Master, Fraí Andrew Bertie, with the High Offices and members of the Sovereign Council (right) and the representatives of the Orderís national and international bodies during the mass celebrated in the Co-Cathedral of St. John the Baptist. |

The episodes regarding Blessed Gerard are also given in the various versions of the Miracula analysed by Joseph Delaville Le Roulx, certainly the greatest modern historian of the Order, in his rare volume, De prima origine Hospitalorum Hierosolymitanorum, published in Paris in 1885. The most famous is the miracle of the stones during the crusader siege of Jerusalem, when Gerard "who served the poor of the Hierosolymitan Hospital, every three or four days collected bread in his lap which he then threw, like stones, over the walls to the hungry Christians". Caught red-handed and taken before the Muslim authorities to be sentenced, the bread was miraculously transformed into stones, forcing his accusers to drop their charges. When the crusader armies entered Jerusalem, Gerard was supposedly rewarded for his action with various gifts and possessions.

Despite its explicitly hagiographic intent, the episode, admirably depicted in a fresco attributed to Lionello Spada narrating the history of the Order in the Grand Masterís Palace at Valletta, revealed a consistent basis of truth, like many medieval legends. This episode should be viewed against the background of the siege of Jerusalem: that is the problems the crusader army had in finding food and water, after the Muslim leaders had ordered the destruction of destroy everything around the city. It is equally true that the donations to the hospital, on which we have the first certain documents, began after the conquest of Jerusalem. In any event, this fabulous story of the origins of the Order of St. John soon found an attentive critic in one of its members, Fra Guillaume de St. Etienne, or William of Santo Stefano, ascribed to the Priory of Lombardy and then, in 1302, Commander of Cyprus. Fra Guillaume was considered to be the author of a critical text on the MIRACULA known as Exordium Hospitali (although this book did not have the success of the Miracula, with had as many as thirteen mentions in manuscripts of the 13th-14th centuries, against the six of the former).

The Exordium, which appeared for the first time in a French manuscript containing the collection of the Statutes, dated 1302 (Paris, Nat. Library, ms. franç. 6049), must have been written around the last decade of the 13th century. This is because another manuscript of the Statutes, again written in French and conserved in the Vatican Apostolic Library (Vat. Lat. 4852), probably written on the initiative of Fra William of Santo Stefano between 1287-1290 and containing the oldest collection of the Rule and Statutes of the Order we have, does not mention this text. Guillaume de St. Etienne is, inter alia, documented in the Holy land, and specifically in Acre in 1282 in a signature on a manuscript preserved in the Condé Museum in Chantilly (ms 590).

The legendary origins of the Order are refuted in the Exordium Hospitalis, as well as those which traced it back to the time of the Maccabees, clearing up the errors and not very credible information narrated in the Miracula. However, also for Guillaume de St. Etienne, the Order originated in the previous foundation of the Amalfi merchants, whose place it took in the buildings adjoining the church of S. Maria Latina, near the Holy Sepulchre. This latter was entrusted for a certain time to the "monacos nigros", probably the Benedictines, albeit there is no explicit documentation on this.

There are also errors and incongruities in the Exordium. This is not surprising as its author did not possess the historical criticism tools we have today. So a document of donation, long considered as the first document made out to Fra Gerard, and attributed to Godfrey de Bouillon, published also by Giacomo Bosio in his famous Historia della Sacra Religione et Illustrissima Militia di San Giovanni Gierosolimitano appearing in Rome in 1594, is in fact a very much later document of Goffredo Duca del Brabante, that Delaville Le Roulx dates to 1183 or 1184.

In fact, a donation from Godfrey de Bouillon to Gerard really existed, and is documented, although it has not come down to us. We are informed of it through a pancarta of Baldwin I, King of Jerusalem and brother and successor of Godfrey de Bouillon, the original of which is preserved in the Orderís Archive in Malta. The document, dated 28 September 1110, confirms all the previous donations of lands and farmhouses and "in primis laudi et confirmo donum quod dux, frater meus, feci Hospitali Jherosolimitano, videlicet do quodan casale quod vocatur Hessilia et de duobus furnis in Jherusalem". This donation from Godfrey de Bouillon must have been dated between the taking of Jerusalem (15 July 1099) and his death the following year (18 July 1100) and constitutes the first historically accepted document of the Orderís foundation.

So that, at the end of the 11th century, when the crusaders appeared before the walls of Jerusalem after having conquered Antioch, the hospital was functioning properly with a structure for receiving and administrating assets, headed by that Gerard, or Gerald as he is indicated in various coeval documents, future first Grand Master of the Order, but of whom nothing is known: neither his provenance nor his status, that is, if he was a religious or not. There were two cities competing for the honour of being the founderís birth place, Amalfi and Martique, a Provençal town under the authority of Manosque, after he finally lost the surname Tunc, which had long identified him in historical studies and papers (and the later variants of Tenc, Tenque, Tenche, etc.). This is because of the obvious fact that the noun "tunc" in Latin meant nothing else but "then", probably written after the name Gerard in a paragraph of some Latin text which narrated his life.

The predilection for Gerardís Provençal origin is supported mainly by fact that, in the first centuries of the Orderís existence, there was a great predominance of Provençal knights, just as they monopolise the list of Grand Masters, starting with Raimondo de Puy, successor of fra Gerard. This however has not meant that the tradition of his Amalfi origin - and specifically from the hamlet of Scala - handed down by the ancient chronicles has not remained alive and in some way favoured by modern historians.

We know nothing of his social condition and if he was consecrated or not. Some have claimed he was a Benedictine oblate, but the documents we have studied testify to the fact that Gerard was not a monk. Annibale Ilari has rightly recalled that, if Gerard had been a religious, Paschal IIís bull of 15 February 1113 addressed to him, with which the Hierosolymitan Hospital was placed under the direct protection of the Holy See, would have had to make explicit reference to it: in fact the document itself should have been addressed to Gerardís superior, that is to the bishop or abbot. Instead, none of the numerous documents regarding Gerard collected by Delaville Le Roulx in his Cartulario, the first volume of which appeared in 1894, makes the least mention of his monastic or clerical condition. He is indicated from time to time as "preapositus", "hospitalario", "priori" and "servus et minister Hospitalis", terms which do not refer to an explicit religious profession. Also the term "fratres", with which Gerardís followers are indicated, had not at the beginning of the 12th century yet assumed that exclusively religious significance it was to have in the Franciscan and Dominican communities. The word "fraternitas", designating the first hospitaller community in Jerusalem, is in fact explicitly cited in the deed of affiliation of Guillaume de Cireza of 4 January 1111.

It is impressive, on reading these documents between 1099 and the year Gerard died, generally placed around the first years of the 13th century, to see the rapid dissemination of the Order not only in the Holy Land, but in all Europe. Gerardís personality, with his commitment to the sick and the needy, must have made an impression on the crusaders who, returning to their own countries, publicised the new institution and pledged to support it or directly become a member.

Paschal IIís document of 1113 photographs a vast area covered "in Asia videlicet vel in Europa" and explicitly cites the Orderís hospitaller settlements in "burgum S. Egidii (St. Gilles), Astense, Pisam, Barum, Ydrontum (Brindisi), Tarentum and Messanam", so much so as to raise a few doubts on the interpretation of the document. However, there can be no doubt about its authenticity after the exhaustive studies to which it has been submitted, of which the latest, by Hiestand, was only a few years ago.

|

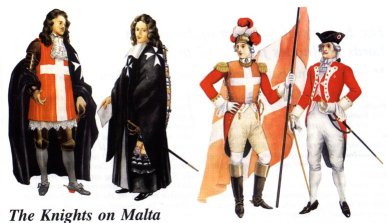

| Uniforms and hobits of te Order during their time on Malta |

It is obvious that Gerard must be considered the founder of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. The letter of Paschal II explicitly affirms this, describing it as an "institutori ac praeposito Hierosolymitani Xendodochio", located in the city of Jerusalem close to the church to St. John the Baptist. Also Callistus II, in the document confirming the privileges of the hospital dated 19 June 1119, again addressed to Gerard, textually affirms that the Xendochium of Jerusalem was "institutum a te".

If there is no doubt that Gerard was the founder of the hospital, at least in its new construction and organisation revealed in the early 12th century documents, it is more difficult to establish when precisely this occurred. We know that Gerard was present and active in Jerusalem when the crusaders conquered the city. He had probably been operating there for a few years before, perhaps in the hospitaller foundation alongside the monastery of S. Maria Latina, said to be of the merchants of Amalfi, thus proving his Amalfi origin.

The creation of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and its consequent legal and structural organisation must have accelerated the formation of the community headed by Gerard, initiated with the aforesaid donation of possession by Godfrey de Bouillon. It more probably occurred in 1099 than 1100, if we consider it a recompense for the services Gerard performed for the crusader army during the siege. It also proves the effective distancing of the "fratres hospitalarii" from the Benedictine monastic community (from which perhaps they derived) and thus of their independence, also involving the need to procure funds and other resources to increase their charitable activities.

During the first decades of the 12th century, the communityís hospitaller activity was predominant, following the rule that encouraged an intense evangelical life spelt out in the three vows of chastity, poverty and obedience. Late on, under Grand Master Raymond de Puy, the military activity also developed and for many centuries rendered the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem famous, first on land and then, after the loss of the last stronghold of Acre, mainly on the sea.

With Pope Eugene IIIís approval of the Rule of Raymond du Puy prior to 1153 the Order, which had already acquired its independence following the bull of Paschal II, confirmed by his successors, provided itself with a valid hierarchical and religious structure, helping it to survive its various vicissitudes over the centuries.

Today, nine centuries since the Orderís creation, the "servitium pauperum" and "tuitio fidei" which were the two distinctive features of the Hospitallers of St. John remain the principal and most significant pledge of the Knights of Malta for the coming millennium.

Thank you!

Giovanni Morello