|

point in the decades before 1206 the Order's military brethren

were divided into two separate classes, the milites or knights

and the military sergeants(13).

Hospitallers and Templars were not monks,

since they did not live in a closed or cloistered community

or devote themselves primarily to prayer; liturgically they

followed the canonical ordo of seven hours rather than the

monastic ordo of nine hours. They were religious who professed

the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience according to a

Rule approved by the papacy. They took part in many crusades

of a certain type but not, technically, as crusaders. The

crusade was a holy war but it was not perpetual; it took place

for a limited period when, and only when, the pope proclaimed

it; it might be directed against the infidel, or against schismatic

Christians or, as in the majority of cases, against Latins

who were enemies of the papacy. A man who took the vow of

the cross could perform his crusading service, receive his

indulgence and return to normal life. By contrast, the holy

war of the military order was perpetual; it was directed exclusively

against infidels rather than Christians; and it did not depend

on any papal proclamation. A Hospitaller was not a crusader;

he had taken a vow of obedience and was therefore not free

to take the crusader vow; the cross on his habit was worn

in remembrance of Christ's suffering and was not a crusading

cross. The Hospitaller's participation in a crusade was not

that of a crusader (14).

The charitable institution which emerged

from the Jerusalem hospital became, alongside the Templars,

a great force in the Latin East, in its political affairs,

its military expeditions and within its society as a whole.

Its Eastern operations may at times have produced some wealth

for the Hospital in the Levant, especially if it could profit

from the Oriental spice trade or from local sugar production

(15). Basically, however, the Order

relied on the Latin West for manpower, for funds and for political

support. In Western Europe came donations, privileges and

exemptions. Lands were organized in commanderies, priories

and provinces which recruited men and sent them to Syria and

which created wealth and transferred it as responsiones or

dues to the Convent in the East. The commandery had many functions:

it was a centre of liturgical life; it managed estates

to create surplus wealth; it recruited and trained brethren

and it housed them in their old age; it maintained, in certain

places, hospices, hospitals and parishes; and it played a

part in local society, maintaining contact with, and securing

support from, the public as a whole. Commanderies and priories

varied greatly; in some regions the priories' estates and

resources were very extensive indeed (16).

|

Along with

a great expansion in the Hospital's power and importance came

a change in its leadership. The Templars had from their foundation

been knights, some from leading families, but the social origins

of the earliest Hospitallers were obscure and only a limited

number of the Hospital's brethren were fratres milites. There

was great diversity between the priories and it was, in any

case, extremely difficult to define a secular miles or knight.

The 1206 statutes distinguished between milites and the socially

inferior and normally less wealthy sergeants, and they referred

to the knighting of sons of gentilz homes. Thirteenth-century

statutes spoke not of nobility but of the obligation that a

brother-knight be a knight before being received into the Order

or, if he were not yet knighted, that he be of knightly birth

(17). By the mid-fourteenth century

a knight-brother was supposed to be noble through both parents

(18) but in practice many were country

gentry or belonged to an urban patriciate of rich townsmen who

may indeed have claimed a form of nobility or at least of knighthood.

In addition to the three categories of priest-brethren, milites

and sergeants, there were also Hospitaller sisters whose numbers

were not inconsiderable. For example, in England in 1338 there

were approximately 116 professed brethren plus a few more on

Rhodes or elsewhere, and they included 31 milites, almost all

of them from relatively obscure families, 34 priests, 47 sergeants

and also 50 sorores; of these, seventeen sergeants and six priests

held commanderies (19). The sisters

did not fight or serve in hospitals or hospices and they seldom

paid responsiones or attended chapters, but they could be important

in maintaining the Hospital's contacts with noble or gentry

families who provided donations or recruits for the Order.

|

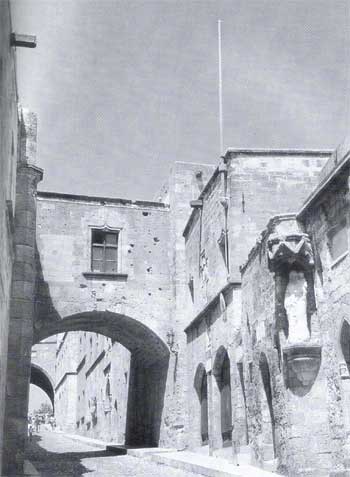

| Rodi. La "Via dei

Cavalieri". |

|

|

[13]Cartulaire,

i, no. 527.

[14] A. Luttrell, "The Military Orders: Some Definitions",

in Militia Sancti Sepulcri, ed. K. Elm - C. Fonseca (Vatican, 1998);

for a different emphasis, J. Sarnowsky, "Der Johanniterorden

und die Kreuzzuge", in Vita Religiosa in Mittelalter: Festschrift

für Kaspar Elm zum 70. Geburtstag, ed. J. Felten - N. Jaspert

(Berlin, 1999). Technically the Hospitallers were not monks, not

crusaders, not Vasalli Christi and not members of a chivalric order,

whose members were not professed religious; nor were most of them

knights.

[15] A large quantity of the special pottery used in sugar

production has recently been discovered in the excavations of the

Hospital's great palace at Acre.

[16] Most priories have been neglected by historians, some

having lost their archives; they require much more study.

[17] Cartulaire, ii, nos. 1143 (pp. 39-40), 3039 # 19 (1262);

the precise dating of these statutes is open to debate.

[18] A. Luttrell, The Hospitallers in Cyprus, Rhodes, Greece

and the West: 1291-1440 (London, 1978), item XIV, 511.

[19] L. Larking, The Knights Hospitallers in England being

the Report of Prior Philip de Thame to the Grand Master Elyan de

Vilanova for A.D. 1338 (London, 1857), provides slightly imprecise

statistics, some brethren being of uncertain status; these are discussed

in G. O'Malley, The English Knights Hospitallers:

1468-1540 (unpublished Ph.D. thesis: Cambridge, 1999), 27-28.

|

|